Come from forever, who will go off everywhere.

Arthur Rimbaud, To a Reason.

SEE IMAGES [1]

THE STRANGENESS OF THESE FACELESS FACES

TIME, HER ONLY CONTEMPORARY

AWAY FROM BELONGING, EXILING ONESELF FROM ONE'S ORIGINS

FAR FROM THEIR NATAL MASS GRAVE

A DEATHLY LIGHT THAT UNCEASINGLY DESTROYS DEATH

IDENTIFYING NOT WITH AN IMAGINARY IDEAL, BUT WITH AN IMMATERIAL IDEA

THE POLYPHONY OF BEING

A FREE SPACE FOR THE PLAY OF TIME

THE UNIQUE IMAGE OF A UNIQUE FIGURE IN THE ANONYMOUS IMPERSONALITY OF THE UNIVERSAL

BEING EVER MORE BY BEING EVER DEEPER IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE SELF

SOMETHING BEYOND WHAT THE IMAGES SHOWS

THE INEXHAUSTIBLE ALLURE OF WHAT LACKS

She smiles, bowing her head, and shoots your way in a clear voice, ‘All that’s not me, that's what interests me’. What does she mean by that? You haven’t the slightest idea but approve, because you suddenly guess that everything having to do with identity, genealogy, even genetics, that religious and social or familial roots—that all that will at last be short-circuited, denied, overstepped. She also has this turn of phrase, which is quite succinct: ‘Each photograph is a ceremony of disappearance’. Let’s wait for what comes next: ‘My self-portraits are still lifes. What I show is the image of a corpse.’ You immediately see what it’s all about: being and nothingness, the vanity of the image, life and death, and especially getting beyond narcissism.

She speaks as follows: ‘To show doesn’t mean giving us everything to see. To look means seeing that something escapes the gaze, that the image leaves something to be desired.’ She insists, ‘What the gaze sees in the image isn’t what it looks at. It is the lack in the image that captivates the gaze.’ So desire concerns only what is lacking? Yes indeed, that’s it all right. And going on, she explains, ‘A work of art is a symptom that is successful, that is, transformed. Art is what transforms.’ Transformation, that then would be the key word in Kimiko Yoshida’s vocabulary.

In passing, she sets you straight, ‘The self-portrait isn’t a reflection of oneself, but a reflection on the representation of oneself.’ You readily believe her when she says she’s turned her back on any ‘quest for identity’ and what goes with it: the narcissistic wound, ceaseless search for an origin, furious demand for belonging, withdrawal into oneself, boredom, humiliation. Naturally the artist rejects the tired stereotypes of communitarianism and its ideology of segregation which lights the period with a peculiar brown light. Her work speaks more of the happiness of being oneself without believing oneself identical to oneself, without identifying oneself with any memory, clan, or family.

We learn that these are Self-portraits, but it is strange to see how little they resemble one another. The other strange thing is that these faces, all so different, tend to blend almost entirely with the monochrome background and disappear there. Who is this young woman who is hiding behind her own mask? Impossible to know really. Where does she come from? Japan, of course, but also much further: Greece, Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt, Judea, Yemen, the Amazon, Africa, New Guinea… She is entering a secret geography, she looks intense and very calm.

What does she wish to show by hiding in bright light? What is she looking at, bent over her inner self? Is she only taking care of you? Isn’t she simply meditating? Levitating? Doesn’t she enjoy a very odd freedom? She’s visibly slipped into the blessed sensation of being. The marvelous turn of phrase is Montaigne’s, ‘It is an absolute perfection, and as it were divine for a man to know how to enjoy his being loyally.’[1]

We look at her and we feel she has indeed entered ‘absolute perfection’. Yes, the artist in her Self-portraits, and beyond any self image, knows how to loyally speak about and enjoy her being. Nothing is asked in exchange, there is no hidden reverse. Seen in this way, art, or what is called thus, becomes natural.

Self-portraits probably, but extricated from the weightiness of resemblance, ripped from psychological ponderousness, freed from universal gravity, ethereal. A sudden extension of a pre-Socratic Eden. Out of range of the usual nihilistic parody, the ambient trashy eroticism, the imposed sentimentalism. An art that isn’t solely ravaged by death. Far, very far from the advancing tide of tensions around the question of identity, the treacherous demands for community segregation, the complacency towards social or religious determinism, the well-worn role of gender and the false values of belonging.

These faces that devour the space beyond the image where they disappear suit me fine. They don’t look like anything and I find them all the more touching. I do recognize, however, in their concentrated, dynamic and universal presence, all the faces of the women I know. In the overturned bubble of Time recaptured, these Self-portraits incorporate all kinds of forgotten rituals and timeless mythologies. They’ve passed through the work of Titian, El Greco, Velazquez, Rembrandt, Fragonard, Manet, Picasso, Bacon, Warhol… They take upon themselves the entire history of the portrait and absorb it. They contain all the Venuses and the Queens of Sheba, the Judiths and the Salomes, the Mary Magdalenes and the Marilyns, the bathing Susannas and the Irises, messengers of the gods, the women warriors and saints, the courtesans and the sultanas… Nudes standing or descending a staircase, effigies seen head-on or in profile, goddesses, bathers, queens, infantas, passers-by, bathers, flowers of evil, young girls in bloom…

THE STRANGENESS OF THESE FACELESS FACES

‘At some night fair in a northern city’, writes Rimbaud in his Illuminations, ‘I met all the women of the ancient painters’. Kimiko Yoshida has done the same. But her Self-portraits remain the height of incongruity with respect to history. One must view and understand the presence, the progressive vanishing and the instant borne by these intense, pacified images. These women are singular. Which renders them even more unsettling. There remains nevertheless the strangeness of these faceless faces, elusive, sumptuous and fragile, levitating in an immobile ether, like a fresh breeze in a clear sky.

Suddenly, there is nothing else but her. She has just loomed up here, in a vibration of the present. The endlessly nullified past. The useless future. There is finally nothing more to interpret. We are only there, before something incomprehensible. We are both inside and out; inside and out are no more. What rest, what silence, what precision. As if the human condition had found its primordial face, incomplete and full, being both absent and revealed.

Kimiko Yoshida, here and now, in broad daylight and yet completely wrapped in mystery, slips into real detachment, where the face of the infinite is revealed. She has arranged to reach this paradise of revealed presence. The ‘ceremony of disappearance’ has been fulfilled and is reversed as pure revelation. The revealed face tends toward the intangible; it is on the verge of swooning in the monochrome background, dissolving in sole colour, disappearing from the image. What appears in the image is firstly disappearance, where the vanished face is revealed as appearance in the process of disappearing. When the face fades under uniform colour, it appears like the disappearance in which what has disappeared possesses still the appearance of what has disappeared.

What we call revelation is just that: the invisible that has become appearance. The image presupposes absence and the erasure of what it represents; it identifies with what subsists in absence. What makes the image possible is the limit where it vanishes, the limit where is shown that which remains when there is nothing.

There lies the ambiguity that the art of Kimiko Yoshida both exhibits and conceals, the ambiguity that is the base on which the image continues to affirm the face revealed in its obliteration. Between the figurative and abstraction: to abstract the face, always subtract, always remove - and to figure absence, erase still, make something disappear still.

The disappearance at work in these images - the image of disappearance, the image as the site of disappearance - discovers for us a more essential obliteration. The image of disappearance has become a disappearance of the image. The obscurity that illuminates the night is finally exchanged for the gentleness of the day beneath a steady sun. Revelation in colour has taken place.

The result is profound.

Portrait of the artist as a fundamental mythological figure: look at these Self-portraits one by one and each time the face is essential, timeless. She could be Phoenician, Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Etruscan, no matter. By turns she is a Gorgon, vestal virgin, martyr, Madonna. She can be at one and the same time Athena, Artemis and Aphrodite, Iris, Circe or Diana, Lucretia and Antigone, Cleopatra, Olympia, Beatrice, Ophelia… The dance whirls around upon itself.

TIME, HER ONLY CONTEMPORARY

We see her, black goddess, white idol, female substance levitating or in ecstasy, casual, profound, sublime, thoughtful, indifferent, concentrated, sure of herself, secret, self-effacing, majestic, aristocratic, silent, ethereal, solemn, excessive, fresh, timeless, priestly, pretty, intense, gay, universal, irresistible, untouchable, happy, desirable, unassailable, rigorous, disturbing, inflexible, sensitive, different… If you think about it carefully, all truths are worth voicing to her, all roles suit her, the rest follows. If you wish to be loved, begin, like her, by loving yourself. And stop boring everyone with the hopeless ups and downs of your so-called identity: the social roots that are bound to be unsatisfying, a family history that’s sure to be unhappy, a gender that raises problems for you, the religious virus that is poisoning your life, the impasse of the ethnic group to which you belong, your doubtful heredity, your vague pathos, your genealogical obsessions offering no way out, your psychological troubles, and partiality for your little difference. Because, beyond the clichés and the conventional banality of your narcissistic demand, you’re most grossly in the general consensus when you believe you’re an exception, and reciprocally when you believe you’re universal, you have really nothing of the exceptional that forces unanimous agreement and appears obvious to all as a factor of truth - the exception being indeed the only position that allows the breakthrough.

Everyone agrees yet almost nobody dares to think about the consequences: the ghetto, the Western paradigm of exclusion and homogenization, signals the failure of universalism. Hence narcissistic segregation, sexual boredom, psychic inhibition, hence psychological withdraw, the family, the clan, the community, the close relation, the ethnic group, hence instinctive racist mistrust, the phobia of otherness, of what is altered, of impurity. And the unrelenting appeals to the fanaticism of the bloodline and the distancing of the Other that follows. To combat the anxiety of contamination, we have to consciously overlook mixture, promiscuity and the mingling of the sexes. The master of the social spectacle desires it to be so, there is too much disorder, in the future the key signifier will be separation, that is, ethnic purification, ethnic cleansing, ethnic purging in the name of the loathsome pleasure of deadly adherence, community, origin.

We see the straightforward opposite approach that Kimiko Yoshida chooses to take in order to respond to that absolute master, which is death and on which the play of history and social decay depend. ‘Death is the absolute master’, says Hegel and we remember. We admire the incredible physical freedom with which the artist implements her response to the absolute master and his deadly play.

Thus, through the self-transformations that she brings off herself, there looms up an African, then an Indian, next a Tibetan, with a detour through Russia, Palestine or Yemen… One woman, then another, then still another… Looming up and disappearing, the faces change and don’t change, they are exchanged in the mists of time, come together elsewhere, differently, and indicate the way out of the circle. Epiphanies and illuminations…

What would we know of beauty without these head-on views of strangeness? Here we find ourselves by turns before the Neolithic Venus, the Aztec priestess, the Amazon warrior, the Eve of Eden, the Pythia of Delphi, the Bachelor Bride stripped bare, the vestal virgin of Pompeii revealing the erect Phallus of forgotten mysteries.

A disorientation of history? An overflow of Time? Might the artist be in the process of creating an art that is above metaphysics, stronger than dialectics of death and life? That is indeed what she thinks. She looks around her and sees that Time is her only contemporary. Her art immediately has the upper hand with respect to oblivion.

No obscure symbolism, no useless irrational mysteries. Kimiko Yoshida shows in colour the ageless beauty illuminating space. But how does true beauty today dare to show itself? See here the moment experienced for the moment, in its form caught at the very instant of awakening, freed from nothingness. Beyond the overvaluing of the negative, far from the falsely hermetic example of a cumbersome style. Simplicity, clarity, subversion itself.

AWAY FROM BELONGING, EXILING ONESELF FROM ONE'S ORIGINS

Wholly in the joy of existing by being oneself other than oneself. To be ‘oneself’, isn’t that to be another constantly? Along with Rimbaud, she maintains that ‘I is another’. But yes, I is divided, it can be several, a play of borrowings and becomings. An ‘I’ that is ‘multiple, impersonal, why not anonymous’, as Mallarmé, the great contemporary of Rimbaud, puts it.

I is another? The expression is too famous to have ever really been read. An endlessly blue-pencilled assertion, wrongly interpreted, that is, hastily understood, mummified, recited without truth. Hegel: ‘What is well known in general, indeed because it is well known, is not known.’ [2].

Do we clearly bear in mind that Rimbaud’s expression, so dazzling and ‘well known’, arose at the height of the insurrection of the Paris Commune? One must read his letter of 13 May 1871,[3] the so-called first letter of the Seer, in which the very young writer speaks of the ‘mad fits of rage’ that are propelling him ‘toward the battle of Paris’. One understands the intimate exaltation, the absolute commitment, the immediate bias in favor of the armed revolt of the workers who were governing Paris and inventing in chaos a new society. In this letter, which ‘doesn't mean nothing’, as one suspects, Rimbaud lays out a powerful programme of ‘riffraffing’. Here it is: ‘To work now, never, never; I’m on strike. Now I’m riffraffing as much as possible. Why? I want to be a poet, and I’m working to make myself a seer: you don’t understand at all, and I can hardly explain it to you. It means reaching the unknown through the derangement of all the senses. The suffering is enormous, but one must be strong, be born a poet, and I’ve acknowledged that I am a poet. It’s not my fault at all. It’s wrong to say, “I think”. One should say, “I am thought”. Excuse the play on words. I is another. Too bad for the wood that finds itself a violin, and tush to the reckless, who quibble about what they are altogether ignorant of!’

A very serious play on words indeed. Inaugural radical experience, which points to Clérambault’s (the first clinical formulation of ‘xenopathic phenomena’: I am thought) and Lacan’s (it is proper to say, not ‘I am speaking’, but rather ‘I am spoken’). In short, I is subject to language: the subject of language is first a subject subjected to language.

Two days later, in the second letter of the Seer, Rimbaud offers ‘an hour of new literature’ to another interlocutor.[4] Here is ‘the prose on the future of poetry’ that the young Rimbaud addresses to the other: ‘Because I is another. Brass wakes up a bugle, it’s not its fault at all. I am witnessing the hatching of my thought: I look at it, I listen to it, I give a stroke with the bow: the symphony begins to stir deep down, or leaps onto the stage. If the old idiots hadn’t found only the false meaning of the ego, we wouldn’t have to sweep away those millions of skeletons which, for an infinite time now, have accumulated the products of their half-blind intelligence, claiming to have created them!’

A stroke of the bow launches the hatching of thought, the transformation of wood into a violin makes the symphony stir deep down, the transformation of brass into a bugle summons poetry to leap up on stage: ‘a rap of your finger on the drum discharges all the sounds and begins the new harmony’, says Rimbaud in To a Reason. Bow, violin, bugle and drum - derangement, symphony, harmony and poetry, here then are the means and the aim of he who was ‘born a poet’ and ‘acknowledged that [he is] a poet’. Music and Letters.

Obviously what counts is neither the wood, nor the brass, nor the ego, but not remaining oneself, getting out of one’s adherence, exiling oneself from one’s origins. What really is important is the changing into a violin, the metamorphosing into a bugle, becoming a poet: transformation, transfiguration, illumination. Opposite which, the bad poetry accumulated ‘for an infinite time now’ by the ‘half-blind’ lack of intelligence of the ‘old idiots’ who only claim to follow the ‘false meaning’ of the ego - those are only ‘millions of skeletons’ that need to be constantly swept away…

Two lines further on, the poet specifies the scope of his anger with the ‘mouldy’ play of ‘idiotic’ literature: ‘So many egoists declare themselves to be writers; there are others who ascribe their intellectual progress to themselves! But it’s a matter of making the soul monstrous… I say that one must be a seer, become a seer. The poet becomes a seer through a long, immense and reasoned derangement of all the senses. All the forms of love, suffering, madness.’

For her part, Kimiko Yoshida doesn’t think her ego is either sacred, untouchable or even independent. Which obviously doesn’t hinder her from loyally enjoying her being, enjoying in absolute perfection the intimacy of her being—or from experiencing ‘all the forms of love, suffering, madness’. In short, she doesn’t have the ‘half-blind’ lack of intelligence to believe she is identical to herself.

From the outset, her works are absolutely escaping from the community-based withdrawal ‘like a falcons flight, far from their natal mass grave’ (Heredia). Images that are foreign to the ambient narcissistic depression, they escape altogether the contemporary regression of ‘identity’ and the religious or gender segregations in fashion.

Kimiko Yoshida rejects this deadly, furious, archaic defence of ‘identity’, the community, nationality - that is her ‘absolute perfection’. No particular adherence defines her, no family, no clan. Obviously, she neither belongs nor adheres to any ethnic, religious or sexual group. She has turned her back on the contemporary epidemics of the affliction of identity: adherence to a religious ghetto, death chambers for one community or another, ethnic endogamy, the humiliated segregation of gender. The artist places herself apart from the depressing nihilism that characterises the global ideology and economy. Her work indeed responds to the globalisation of goods and images by cutting across constituted cultures and religions, mixing references amongst them, and metamorphosing them. She opposes the clashes between linguistic communities and national belonging by blending rites and mythologies, crossbreeding and transforming them.

Do we know how to hear her? Nothing is less certain.

We need to recall these words written by Rimbaud in his second letter of the Seer: ‘When woman’s infinite bondage is broken down, when she lives for herself and thanks to herself, man - abominable until now - having given her her dismissal, she too will be a poet. Woman will find the unknown! Will her worlds of ideas differ from ours? She will find strange, unfathomable, delicious things; we will take them, we will understand them.’ [5]

The moment has indeed come to understand.

Kimiko Yoshida explains to you that identity is a fantasy, an imaginary projection, that it is but a thumbing through of a succession of borrowed identities. She truly thinks that identity does not exist, that there are only identifications. Identity is therefore only a card of imaginary identifications, a many-layered pastry of delusions and pipe dreams, superimposed mirages, sundry captures, miscellaneous fictions. The ego is of course not what is weighing down Kimiko Yoshida’s Self-portraits. She doesn’t doubt that the ego is that ‘function of ignorance’ weighed down with an ‘illusion of independence’,[6] that lumber room of delusions and semblances, that superimposition of imaginary peels without a core, whose fundamental inconsistency was exactly what Lacan brought to the fore: ‘The ego is an object that is made like an onion, you can peel iherediat and you will find the successive identifications that have formed it.’ [7]

The question that Kimiko Yoshida remembers surely doesn’t involve an insignificant ‘Who am I?’ But her work does open on the more pertinent and essential question of identifications: ‘How many am I?’ Which obviously has quite a different impact.

A radical impact that goes right to the heart of the image, so long as we look to think what represent means. Baudelaire is amongst those who think that the multiplicity which lies at the origins of representation lies as well at the heart of the ‘individual’. We should reread that notation in Rockets: ‘To glorify the cult of images - cult of multiplied sensation. The pleasure of multiplying number. Ecstasy is a number. Number is in the individual.’ With this question - ‘How many am I?’ - it is the number in her that interests Kimiko Yoshida.

What the artist is attempting to voice precisely is ‘the place where Being unfolds’. Heidegger refers thus to the poetic experience of thought: ‘That character of thought, that it is the work of the poet, is still hazy. Where it can be seen it is long held to be the utopia of a partly poetic mind. But the poetry that thinks is in truth the topology of Being. To Being it states the place where it unfolds.’[8] What the artist tries to think in images is the interstices, intervals, revisions, borrowings, borders, annexations, atomisations, reappropriations, impurities, dismissals, repressions and illusions that are consubstantial with identity: the unconscious imaginary identifications, the chance alterities, the unknown heterogeneities.

In Kimiko Yoshida’s work, history is seen from an angle, at once in vain and saved. Ancient rituals, forgotten mythologies, magical liturgies begin again, differently, coming from elsewhere. A History has taken place, another moves ahead: we can see it, sense it, analyse it, guess at it and expose it, again, with a joyous disquiet. ‘My self-portraits are still lifes. What I show is the image of a corpse.’ And the artist adds: ‘To recapture the particular light of traditional Japanese houses, that subtle light described by Tanizaki in his In Praise of Shadows, I use soft lighting (two 500-watt tungsten bulbs) that professionals generally use to photograph objects. What I photograph as a still life is my own body, in the form a corpse’

Looking superficially at these perfectly beautiful images, how could we ever imagine the essential hidden combat that takes place in a deathly light that unceasingly destroys death? ‘There is no handsome surface without a frightening depth’ (Nietzsche). Not only does this artist avoid sentimental, romantic and depressive platitudes, but she even takes death and nothingness for her partners. We then discover in these images an assured formalism, a metaphysical art in her concentrated minimalism which, in this realist and naturalist age of ours, may seem even more incongruous than ever. No doubt, metaphysical incongruity is untenable when faced with contemporary artistic practices. No doubt. However, a key witness, Sollers, contradicts this propaganda: ‘“Metaphysical” means that nothing, neither time nor space, neither birth nor death, neither language nor life, and even less one’s identity, strike one as self-evident.’[9] Even today, then, there is a French writer and a Japanese artist for whom it is not inconceivable that ‘personal’ identity should not be self-evident.

For Kimiko Yoshida, everything comes down to absence, disappearance, obliteration. But it is all a matter of transformation, connection and reversal: metamorphoses of the body, changes of meanings. Absence is the presupposition of every image, which only ever represents that which is lacking. However, disappearance itself is the condition of revelation. Erasure is overturned into epiphany.

These images erase, reduce, unmake, recompose. The figure is enveloped and dissolves in colour, evaporates in the monochrome, is often abstracted behind an object floating in the foreground. The object is there, now a treasure kept in a museum. Civilisations have disappeared, rituals have been performed, no doubt, but it was a long, long time ago, when there were still tribal chiefs and leaders of the horde, shams and fetishers, initiation rituals and magical funerary rites. It was, then, a long time ago, in the Neolithic era, in the Bronze Age, in the time of the pharaohs and the Inca emperors.

Science, elegance, violence - everything is subjacent, waiting. All the cold power of these images is here, in the subtly tensed, contained, restrained form. No pathos. The lyricism is on the inside. No chitchat, simply allusion, lightness of contact, self-effacement. No expressionism, minimalism holds at a distance all outpourings of suffering or wretchedness. It has been demonstrated that there is no need to go in for caricature or parody to hold your gaze. You are positively invited to see Time, to listen to the silence, to meditate on impermanence, to smell an insolent fragrance of exception, held in reserve.

IDENTIFYING NOT WITH AN IMAGINARY IDEAL,

BUT WITH AN IMMATERIAL IDEA

These deliberately bare works present the same face, a plain ground, a single colour, an object, often unique, that hides the face. But this deliberate concentration on an invariable number of motifs, this minimal, ascetic grammar opens onto a sensitive and subtle register. Structured minimalism and taut formalism here make us feel the fluid, free play of seduction, in a joyous, limpid and meditative resonance. Today’s censors consider seduction a particularly dangerous art. Ugliness is a fact, unhappiness obligatory, suffering encouraged: the horizon is depression. They can give you an injection whenever they want the right dose of concentrated anxiety. It is good that you should live in a state of unease and perplexity. Here, though, we can see that we are about to go blithely beyond these inhibitions. Here, everything will be brought to bear against ugliness, unhappiness and suffering. Here, everything goes lightly and naturally against depression and against anxiety.

For Kimiko Yoshida, the aim is simply to move, lightly and naturally, towards detachment. Detachment, is that what she finds in self-effacement? See the image of that face about to melt into the ground, that makeup melding with the single colour, that face dissolving in the monochrome. One can sense that in such an image significations are reversed, meaning is subverted, representation escapes its presuppositions. Suddenly, we understand that the artist takes her makeup from the Japanese technique of shironuri, the white paint with which geishas and maïkos traditionally cover their faces. Now, this Japanese tradition reverses the very value of makeup: everything runs counter to the significance that the West attributes to this artifice.

Western makeup is conceived to embellish, to magnify. It is made to make a face at once more singular and more beautiful, younger and more perfect. Shironuri tends only to erase the singular face, to dissimulate it by covering it with white, to remove any particularities. A Japanese woman whose face is thus covered with white is therefore not seeking to hide her defects, or to approach perfection, or to singularise herself. She simply wants to have a generic form, to be one with an essential face, to be indistinguishable from an archetype. Her makeup is the white mask that hides particularities, blanks out both qualities and imperfections, erases individuality.

The point, then, is to identify with the idea of a woman and not with an ideal woman, to merge into an abstract idea and not to raise herself up to the dignity of an ideal of perfection. Japanese makeup is the idea against the ideal. Abstraction against perfection. The archetype against singularity. The outcome is detachment from all will to singularity, uniqueness, originality. The path, the only recommended path is in obliteration, detachment, universality. We can thus understand the suspended position in which Kimiko Yoshida places herself, between figuration (her face) and abstraction (shironuri). Her aesthetic of obliteration is thus, in the intimacy of the immaterial idea, a continuous summons to the impersonal, that is to say, to illumination. Her Self-portraits are anonymous and universal, seeking to express, through the geisha’s shironuri, that impetus towards the unattained, towards the idea, towards the immaterial.

THE POLYPHONY OF BEING

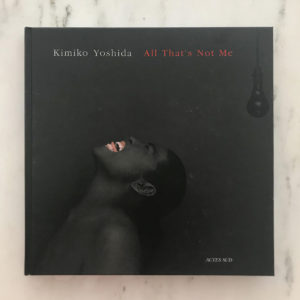

After allowing her access to all the different precious objects kept in the different ethnographic or archaeological departments, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem organized an important exhibition of the works that the artist had made with these treasures. Kimiko Yoshida’s chosen title for this show, All That’s Not Me, implied that what interested her was everything that is other, everything that is foreign to her, and that this was what she chose to show because this, it seemed to her, was the content most worthy of a major exhibition. We are a long way here from the narcissism of small differences, far from mouldering communitarianism, from the Pavlovian reflex of family correctness. The artist simply put the case, with Montaigne, that, ‘We are all framed of flaps and patches and of so shapeless and diverse a contexture, that every piece and every moment played his part.’

Kimiko Yoshida therefore disappears behind the reality of identifications, keeps to the background, hardly mentions herself. She uses herself only in order to talk about something else. She claims as many masks as possible in order to neutralise pathos as much as she can. The truth is that she really does believe, like Pascal, that the self is hateful. She really does believe with Malraux that the ‘little heap of secrets’ and with Nietzsche that the ‘intimate cattle’ are what is least interesting about an artist.

Her Self-portraits lower the curtain on the sameness of being. Winnie’s verdict, in Beckett’s Happy Days, also applies to the life chosen by the artist: ‘To have always been what I am, and so changed from what I was.’

The polyphony of being—that is her chosen course, and we can understand that this option is philosophical as well as aesthetic. We surmise, then, that this polyphony is the foundation of the artist’s ethics, an ethics of mixedness, transformation and impurity. We also grasp the fact that this polyphony could be the political answer to the segregationist dead-end of community confinement, to the nihilistic aberration of these fixations on identity characteristic of the global era.

It is so happens that it is not in her native culture, but in Europe, and more particularly in France, that Kimiko Yoshida implements this essential polyphony, that she gives life to this choir of strangenesses, this bursting of heterogeneities and these transformations. Far from the current auto-fiction where naïve and confused expressions of the “self” dominate and go round in circles, the I that she puts into action invokes the other. It is indeed the other that constitutes the I that constitutes me. That alterity is inseparable from the constitution of any self-image, inseparable from any representation. ‘All that’s not me, that's what interest me.’ And this is the only I evoked by the Japanese artist, in images where she only ever presents herself as other, where she presents only alterity itself. Like the unveiling of an idea, like the interpretation of a vulnerability, or even like the appearance of a corpse that contradicts narcissistic nihilism. The image of becoming-other without denial or irony, without tragedy or expressionism.

An image of the self, then, that does not spare or forbid itself transcultural references or transhistorical meanings, that is unceasingly revisiting them, deconstructing them and unfolding them in images, allusions, metaphors, metamorphoses, masks and personae, fictions, crossed or reversed transformations, a succession of transfigurations, of annexations and illuminations. An image that tries to rethink in images its own meanings and references, an image conceived in the necessity of thinking its own presuppositions, a thinking that integrates the analysis of what makes it possible: epistemology and semiology, formalism and minimalism, subtraction, addition, hybridization, appropriation, reappropriation, ritual, psychoanalysis, crossbreeding, aesthetics, sensibility, the mixing of genres, the very immateriality and polyphony of thought, everything that enables Kimiko Yoshida to test art as the most daring, most radical and freest experiment in voicing the lack-in-being, in converting the symptom, in transforming suffering and unhappiness, in forging past devastation and despair.

A FREE SPACE FOR THE PLAY OF TIME

What, then, is the image of this I? What but the kaleidoscope of a subject on trial and in process, of a self constantly becoming another, of an alterity developed in the élan of a Beckettian ‘without self’. ‘Where now? Who now? When now?’ These are the three questions that open Beckett’s The Unnamable and they are the questions asked by Kimiko Yoshida’s Self-portraits. We will bear in mind, here, that for this artist ‘every image is a ceremony of disappearance’, a ritual of self-effacement.

Is not the unnamed of the work that which opens a ‘free space for the play of time’ (Debord), is it not that spacing of duration that engenders an un-location of time: where now?

Is not the unnameable what is proclaimed by that eternal return, that irruption of vertical time in time: when now?

Is not what remains unnameable in the work the ‘identity’ of the author considered in terms of the free play of time: who now?

Behind the mask of a fascinating dispossession, which does not evade the absolute abandonment of the self, the artist becomes absence, a disappearance dissimulated behind the shadow of an impersonal, neutral anonymity. The supposed identity that Kimiko Yoshida shrugged off like an empty depth unrelated to her fixes itself outside her like the unreality of the indefinite. To try to fix identity, this artist has understood, is to go astray in an unbroken vagrancy, in the saturating obsession of the lure of a elusive something that is impossible to seize, that has no fixity of any kind, that never returns to its place and that is only the empty intimacy of an ignorance unaware of itself.

She has recognized that there is, in the deceptive and strange fascination with identity, a remarkable intention to abolish the future, to close the dark store of possibles. To identify with an identity is to take one coincidence for another, like a kind of strange parapraxis; to know nothing and seek to remain riveted to the empty intimacy of that ignorance. This identity over which I have no power and that has no more power over me because it has nothing to do with me, remains an ordering of encounter, a superficial matter of chance, alien to decision. It is the undecided, uncertain vestige, an indeterminate shadow attached to an epitaph without density, without consequence and, one might say, without a future.

The felicitous, detached freedom with which Kimiko Yoshida moves towards the disappearance of identity makes evident the unreality of the self, the instability of the imaginary, the porosity of identification. Once represented, the I loses the plenitude of its putative unity, unable now to attain itself in the representation of the self. The I that is represented disappears, is no longer me but another, so that, when I represent myself I needs must disappear, since I am not the one I am showing. What appears then is disappearance, in a kind of sovereign casualness, an alliance with the revelation of the invisible, a pact with the reversed negative. The art of Kimiko Yoshida makes its nest, we might say, in that vacancy. Thence there comes to it a call that draws it towards an essential instability where being recognizes itself in the possibility of non-being, where identity is no longer identical to itself, where nothingness conceals itself, where everything is in play - the right to step back, the possibility of disappearing, the power to die.

The experience is worth pondering

These Self-portraits are an attempt to make representation possible by grasping it at the point where what is present is the absence of all figures. The state of invisibility is not the point where the artist presents herself, it is the point that she presents. She feels deeply that the state of invisibility that she presents is related to the radical exigencies of art, that it is not a simple deprivation of visibility or a psychological state particular to her.

To represent oneself via the self-portrait - and this is something that Kimiko Yoshida experiences frontally - is to enter into the affirmation of the solitude where anonymity threatens, it is to give oneself up to the risk of obliteration where anonymity reigns. By imagining an image aiming at pure vision, the artist purifies the presence of absence, she herself becomes ‘the one who is absent in all bouquets’, as Mallarmé put it in a formulation pointing up the essential lack hidden at the heart of representation. She exposes herself to the disappearance of the self, to the disappearance of the persona’s mask. She abandons herself to the impersonality of symbolisation, to the impersonality of death.

‘Where am I? Who am I? A simple passenger in the eternal return of Salvation. But yes, of Salvation’, concludes, simply, the narrator at the end of Une vie divine. The author - that is to say, Sollers, or the narrator, who is also Sollers, or Nietzsche, about whom he is talking, or again Odysseus, who has already named that unnameable - ‘is called Nobody in person. All the names in History can be him: Nemo, Nihil, Nul, Nobody, Nothing, Néant, Nicht, Nichtung, Nessuno, Niente, Nada, Nadie’.[10]

IN THE ANONYMOUS IMPERSONALITY OF THE UNIVERSAL

Kimiko Yoshida does not believe that identity is either graspable or ungraspable, either finite or infinite: it is, and nothing more. Beyond being, identity is nothing. It is - and whoever tries to make it express more will find only that it expresses nothing. Identity is, has no goal and no use. It cannot be identical to itself. No truth can grasp it and no contradiction can be opposed to it. It is undecidable and cannot be verified. No evidence, no certitude can render it more certain or more real. Only renown lights it with the weight of symbol. It is sociology or ‘community’, family or the police that endow it with the only substance has - in the imaginary. In this sense, identity is one with the body: both make an image, consist of an image. The body and identity are, exactly, imaginary. Better, identity is, in representations of the self, the image that is absent from its place; it is the image of a lack.

In the image of the self that the artist seizes, what she grasps in the form of an image is never anything other than the approach to what is lacking, a substitute, a stand-in. Kimiko Yoshida tries this lack and knows only that the work, once made, anonymously closes over the fading of its author; it closes over the mute affirmation that identity, ultimately, is impersonal; it closes over the anonymous impersonality of the universal. Identity does not belong to itself any more than it belongs to a “person.” It is - in the unique totality of its unfinishedness, in the rigour of its inessential incompleteness, in the privilege of its infinity.

But how does this come about?

See the artist in her ‘vibratory almost-disappearance’, as Mallarmé put it, disappear into the monochrome of her image: what we see is not the image of a model but a model image. What the artist shows is not herself. What she shows is an image. The image takes precedence, becomes the essential. This means that the image does not primarily aim to designate or show someone, but that it designates or shows primarily a representation. Only the image is present; that of which it speaks of disappears in what it shows. In this sense, only the work is presence - a presence that oscillates with its presence as an image in the absence of what it represents.

In this perspective, the art of Kimiko Yoshida tends towards the essential. It is an art that moves towards its essence, which is not to reproduce the figure of its model, but to compose with light and colour a figure that is the unique image of a unique figure and not the figure of someone. It is not truth that is its horizon, but the glory of figuring, of evoking in its absence an object, the glory of being an image that is constituted from an absence and imposes itself beyond this absence in the form of a real presence. The image is the presence of an absence. That is what the work makes real, endlessly seeking what it lacks.

The work raising itself to the dignity of the universal demands that the artist lose her identity, that she renounce all individuality and that, ceasing to relate this singularity that constitutes its self, it becomes the anonymous exception where the impersonal figure of unanimity announces itself. This demand does not obtain for Kimiko Yoshida, for her Self-portraits have no identity content; all she seeks to capture is the air in which she must breathe, the wear of the day in which the face familiar to her disappears. Through the immemorial experience of exile, the infinitely reprised traversal of cultures and mythologies both foreign and familiar, the Japanese artist experiences the enigma of the world by relinquishing herself and abandons herself to the infinite impurity of migration and mixing, in the profundity of the indefinite, in the essential infinity of the universal.

IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE SELF

Kimiko Yoshida creates images in a kind of exclusion from which she excludes herself, just as she is excluded from herself, in an experience that is that of the endless flight ‘outside of the native charnel house’. Far from justifying the genetic flow from which she issues, she appraises it from outside, she marks it, judges it, annuls it, forgets it. This possibility of moving forward right to the end of exile transforms what is a wrenching away from the necessity of the origin, from the doxa of family, into an infinite metamorphosis in which the artist enters into her own self-effacement and into the seeking of self-forgetting. A self-forgetting that does not lead only to fading and disappearance, but makes death itself disappear in the infinite movement of disappearing, as if it were a matter of being ever more by being ever deeper in the transformation of the self.

This whole chain of metamorphoses, of modifications, of mutations, this series of methodical distancings that indefinitely deepen the interrelations and transform their goal (to figure) into obstacles (obliteration), but also transforms obstacles into a path to the goal being sought, this impeccable series of images does not figure the higher truth of the world or even its transcendence. Rather, it figures the jolts and pleasures of figuration, of that necessity whereby fiction becomes a means of truth and illusion the possibility of delighting in the invisible.

Kimiko Yoshida annexes mythologies, diverts rituals, transforms their meaning. Her experiences write a new way of living that is colourful, abundant and supple, a new way of coming and going through cultures and religions, now inside, now outside, now in such a language, now in another. She shows her life in division, fragments, the mixing of genres, displacement, collage. It is the freest, most joyous and most conscious contemporary existence, the extreme, indivisible artistic experience, which affirms that it alone is the true apex of the real.

It is an act of light against all violent and murderous obscurantisms now active. It would be hard to be more complete, richer and more beautiful. It looks simple, but it is not. There is, in this concern for self-effacement where the polyphony of being is affirmed, a contemporary life finding its justification.

But the artist never knows what work she has made. What she has made is an image and what she made when making an image she destroys or begins anew in another image. In this sense, we must allow that the author is separate from her work, that she cannot have it, that her only possibility is always to go on creating this work that is always false in relation to herself. The impossibility of ceasing to create is, for the artist, the discovery that in the space opened by what she has created there is no more room for her. She who creates is in exile when she creates; she who creates is still in exile when the work is created. What the artist discovers - what, in the work, belongs to her - is always this absence, this exile, this lack that is before the work and that is the cause of her dependence in creating. To understand that at the end of the work the artist comes again to the very exile that had led her to undertake the work also enables us to understand the feeling of infinity that she has in this necessary new-beginning, in this inability to pronounce the end that is lacking, in this experience of what is unceasingly being written.

We can say: the artist is there where the work is not done: there where the work is, the artist ceases to be. To create is to reject the convention of identity; it is to withdraw the social bond from the course of the world; it is to wrest what I create from its cause. To create is to lose the power of saying ‘I am speaking’ the moment the work pronounces its irrevocable ‘I am’. To create is to identify oneself with what cannot cease to be and, because of that, because she identifies with being, the artist must in way disappear from her work. For Kimiko Yoshida, to represent herself is to disappear under an image and, consequently, to enter into contact with absence becoming an image. To disappear in pure colour is to cause the colour that alludes to a figure to become an allusion to what has no figure. The image, which is that form drawn on absence, then becomes the formless presence of that absence. The single colour becomes the opaque opening onto what is when there is only the void.

Why should figuring have something to do with this essential absence, this absence such that in it alone disappearance appears? That an image fascinates, this happens when it concentrates within itself the blinding and enchanting allure of what it lacks, this ontological lack that is present in all images and that provokes fascination. When the gaze is fascinated, what it sees in the image is not what it looks at, what seizes it and captures it is not in the image that it beholds but in what it lacks, what fixes the cause of fascination in something beyond what the image shows. The fascination is fundamentally linked to this neutral and uncontoured presence of an indeterminate and figure-less opacity within the figure. This hole of opacity within the figure, this hole that hollows the heart of the image with absence, when picked up by the gaze, produces a kind of disquiet and attraction. With Kimiko Yoshida’s aspiration to disappear into pure colour, absence becomes visible, because it is blinding.

The gaze is drawn into an immobile movement, absorbed in a ground without depth. What it is given to see by this distanced contact is the blinding fascination of what it is not possible to see. The gaze uncovers the cause of its desire to see only in what is out of reach, what is lacking in the image, which opens an unfillable gap in the visible. Thus the gaze finds the cause of its desire to see precisely in what is not shown. And it is in what makes it possible that the gaze finds the power that neutralises it, that puts it off balance by preventing it from ever having done. This is where we see revealed the power of the fascinum, which is what exceeds the gaze, that points it, in a vision that never ends, towards the point that captivates the gaze and does not belong to the reality of the image. The fascination provoked by that which is lacking in the image is not the impossibility of seeing, but it is now the impossibility of not seeing. The fascination does not arise from the impossibility of seeing (the invisible), but from the impossibility of not seeing the lack that lies in the image, the punctum that hollows out the visible and makes it desirable. And never ceases.

THE INEXHAUSTIBLE ALLURE OF WHAT LACKS

What is essential in Kimiko Yoshida’s image is that it shows above all the point within it that dissimulates it; it has within it, through this power of dissimulation, the power specific to the imaginary that confers spontaneity and innocence on semblance.

This is because, as we know, the image has the power to make beings and things disappear, to make them appear as having disappeared, to make them appear in their absence, to give them an appearance that is only that of a disappearance, the appearance of a presence that speaks only of absence. However, Kimiko Yoshida’s work shows that the image, by its power to summon the appearance of a being within its absence, also has the power to disappear into it itself, to fade away in the middle of what it accomplishes, to cancel itself there as it proclaims the plenitude of what it endlessly shows and obliterates.

This experience no doubt orients us towards what we seek in her work. We can no longer be unaware of what the young woman brings to her art by disappearing in her image, by disappearing from her image, by making an image of disappearance appear there. She in a sense brings to her art the authority of her own disappearing. She makes palpable, through her silent self-effacement, the indistinct revelation on which the image, by opening to what it is beyond it, becomes an empty plenitude whose very gape is what eroticizes the gaze. This ‘plenitude’ is ‘empty” because it fully designates that there is in the image a blinding, invisible and empty lack. It is not without significance that these are the qualities from which Kimiko Yoshida has formed the title of one of her works.[11] This blinding, invisible and empty lack is what defines the beyond that is precisely what the gaze desires to see.

This gap hollowing out the image, which is the resource of her art, has its source in the disappearance to which all artists are invited, and especially when they invoke their own image. Kimiko Yoshida trusts in the endless blinding light of that which lacks - again, the title of one of her works.[12] Being deprived of herself, having renounced herself, she has however, in that self-effacement, maintained the authority of a power, the decision to disappear, so that - in this fading in the monochrome - form, coherence and pertinence are bestowed on the affirmation of what is. Without end. Without beginning.

This power is not mastery, but the intimacy of the obliteration that the artist imposes on the figure of her own self, whereby this obliteration is indeed her obliteration, that which remains of her in the discretion that puts her to one side and, yet, still reveals her to the gaze. In the monochrome, the singular figure (“self-portrait”) disappears so as to give voice to a universal. In the depth of the colour, the possibility of appearance and revelation takes the place of disappearance and obliteration.

By transforming herself Kimiko Yoshida gives herself a unique chance to raise her project towards an impossible that transcends her. By affirming the absolute right to successive and simultaneous identities that are at once fictional (each self-portrait as a Mariée (Bride) speaks of a bachelor bride) and contradictory (The King of Judea Bride, The Demoiselle d’Avignon Bride, etc.), by affirming the absolute right to disappear in the self-effacement, in the metamorphosis of the self, Kimiko Yoshida affirms the only right that is the obverse of no power, a madness requisite solely for the raison d’être of art, which is to transform what art alone can transform. Her art, by appropriating heterogeneous mythologies and rituals, by taking from painting its structure of representation so as to abolish all representation, gives the idea of a rigorous unrepresentable, unlocatable space, the idea of a space beyond the image where representation exceeds the space of representation.

Ultimately, for Kimiko Yoshida art is above all the experience of transformation: ‘Transformation is, it seems to me, the ultimate value of the work. Art for me has become a space of reversal, of free resonance, of shifting metamorphosis - mutation, permutation, transmutation. My self-portraits, or what go by that name, are only the place and the formula of the transfiguration. All that’s not me, that's what interests me. To be there where I think I am not, to disappear where I think I am, that is what matters.’

Suddenly, the past is abolished, the present becomes constant, the future is sucked in. These photographs impose themselves like a succession of epiphanies; a precise sequence, present and transparent, of thought. There is nothing like this thinking in images to affirm Time and reverse it before your eyes, to transform, recover, breathe, isolate, space, listen, pour out, concentrate, dilate, contract, accelerate, brake and multiply time.

Jean-Michel Ribettes.

Translation by Charles Penwarden.

Exhibition at The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel, 2006.

Catalogue All That's Not Me, Actes Sud, 2007.

Notes:

1 - MONTAIGNE, Essays, III, 13.

2 - G. W. F. HEGEL, preface to The Phenomenology of the Spirit.

3 - Arthur RIMBAUD, letter dated 13 May 1871 to Georges Izambard, called the "first letter of the Seer".

4 - Arthur RIMBAUD, letter dated 15 May 1871 to Paul Demeny, the "second letter of the Seer".

5 - Idem.

6 - Jacques LACAN, Écrits, Seuil, 1966, p. 99.

7 - Jacques LACAN, Les Écrits techniques de Freud, 5 May 1954.

8 - Translated from Martin HEIDEGGER, "L'expérience de la pensée", in Questions III, Gallimard, 1966.

9 - Philippe SOLLERS, Éloge de l'infini, Gallimard, 2001, p. 412.

10 - Philippe SOLLERS, Une vie divine, Gallimard, 2006.

11 - Cf. the series of abstract monochrome photographs entitled L'Instance de la lettre, 2004-2005, in Jean-Michel RIBETTES, D'une image qui ne serait pas du semblant. La Photographie Écrite 1950-2005, Paris-Audiovisuel/Passage de Retz, 2005, p. 178-181.

11 - Ibid.